转载自 https://martinfowler.com/bliki/CircuitBreaker.html

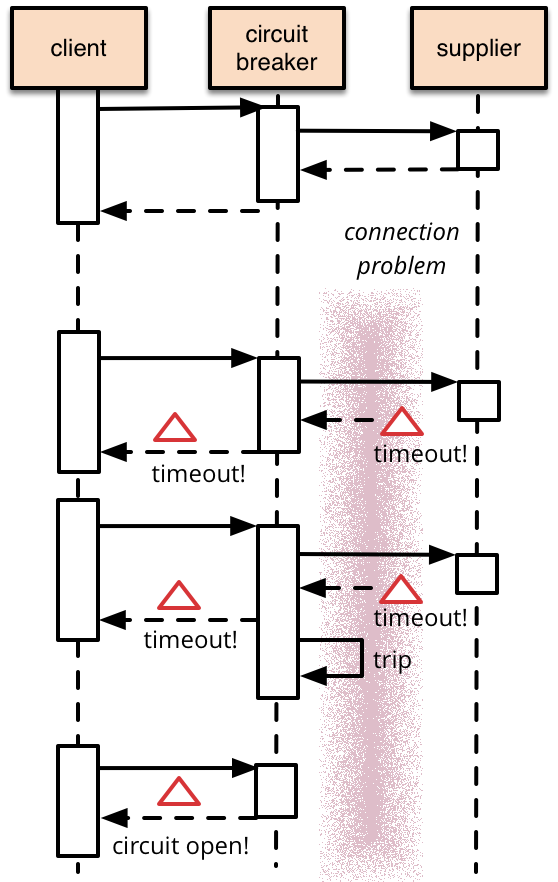

It‘s common for software systems to make remote calls to software running in different processes, probably on different machines across a network. One of the big differences between in-memory calls and remote calls is that remote calls can fail, or hang without a response until some timeout limit is reached. What‘s worse if you have many callers on a unresponsive supplier, then you can run out of critical resources leading to cascading failures across multiple systems. In his excellent book Release It, Michael Nygard popularized the Circuit Breaker pattern to prevent this kind of catastrophic cascade.

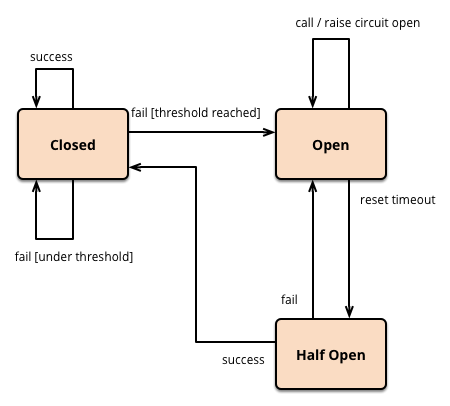

The basic idea behind the circuit breaker is very simple. You wrap a protected function call in a circuit breaker object, which monitors for failures. Once the failures reach a certain threshold, the circuit breaker trips, and all further calls to the circuit breaker return with an error, without the protected call being made at all. Usually you‘ll also want some kind of monitor alert if the circuit breaker trips.

Here‘s a simple example of this behavior in Ruby, protecting against timeouts.

I set up the breaker with a block (Lambda) which is the protected call.

cb = CircuitBreaker.new {|arg| @supplier.func arg}

The breaker stores the block, initializes various parameters (for thresholds, timeouts, and monitoring), and resets the breaker into its closed state.

class CircuitBreaker... attr_accessor :invocation_timeout, :failure_threshold, :monitor def initialize &block @circuit = block @invocation_timeout = 0.01 @failure_threshold = 5 @monitor = acquire_monitor reset end

Calling the circuit breaker will call the underlying block if the circuit is closed, but return an error if it‘s open

# client code aCircuitBreaker.call(5) class CircuitBreaker... def call args case state when :closed begin do_call args rescue Timeout::Error record_failure raise $! end when :open then raise CircuitBreaker::Open else raise "Unreachable Code" end end def do_call args result = Timeout::timeout(@invocation_timeout) do @circuit.call args end reset return result end

Should we get a timeout, we increment the failure counter, successful calls reset it back to zero.

class CircuitBreaker... def record_failure @failure_count += 1 @monitor.alert(:open_circuit) if :open == state end def reset @failure_count = 0 @monitor.alert :reset_circuit end

I determine the state of the breaker comparing the failure count to the threshold

class CircuitBreaker... def state (@failure_count >= @failure_threshold) ? :open : :closed end

This simple circuit breaker avoids making the protected call when the circuit is open, but would need an external intervention to reset it when things are well again. This is a reasonable approach with electrical circuit breakers in buildings, but for software circuit breakers we can have the breaker itself detect if the underlying calls are working again. We can implement this self-resetting behavior by trying the protected call again after a suitable interval, and resetting the breaker should it succeed.

Creating this kind of breaker means adding a threshold for trying the reset and setting up a variable to hold the time of the last error.

class ResetCircuitBreaker... def initialize &block @circuit = block @invocation_timeout = 0.01 @failure_threshold = 5 @monitor = BreakerMonitor.new @reset_timeout = 0.1 reset end def reset @failure_count = 0 @last_failure_time = nil @monitor.alert :reset_circuit end

There is now a third state present - half open - meaning the circuit is ready to make a real call as trial to see if the problem is fixed.

class ResetCircuitBreaker... def state case when (@failure_count >= @failure_threshold) && (Time.now - @last_failure_time) > @reset_timeout :half_open when (@failure_count >= @failure_threshold) :open else :closed end end

Asked to call in the half-open state results in a trial call, which will either reset the breaker if successful or restart the timeout if not.

class ResetCircuitBreaker... def call args case state when :closed, :half_open begin do_call args rescue Timeout::Error record_failure raise $! end when :open raise CircuitBreaker::Open else raise "Unreachable" end end def record_failure @failure_count += 1 @last_failure_time = Time.now @monitor.alert(:open_circuit) if :open == state end

This example is a simple explanatory one, in practice circuit breakers provide a good bit more features and parameterization. Often they will protect against a range of errors that protected call could raise, such as network connection failures. Not all errors should trip the circuit, some should reflect normal failures and be dealt with as part of regular logic.

With lots of traffic, you can have problems with many calls just waiting for the initial timeout. Since remote calls are often slow, it‘s often a good idea to put each call on a different thread using a future or promise to handle the results when they come back. By drawing these threads from a thread pool, you can arrange for the circuit to break when the thread pool is exhausted.

The example shows a simple way to trip the breaker — a count that resets on a successful call. A more sophisticated approach might look at frequency of errors, tripping once you get, say, a 50% failure rate. You might also have different thresholds for different errors, such as a threshold of 10 for timeouts but 3 for connection failures.

The example I‘ve shown is a circuit breaker for synchronous calls, but circuit breakers are also useful for asynchronous communications. A common technique here is to put all requests on a queue, which the supplier consumes at its speed - a useful technique to avoid overloading servers. In this case the circuit breaks when the queue fills up.

On their own, circuit breakers help reduce resources tied up in operations which are likely to fail. You avoid waiting on timeouts for the client, and a broken circuit avoids putting load on a struggling server. I talk here about remote calls, which are a common case for circuit breakers, but they can be used in any situation where you want to protect parts of a system from failures in other parts.

Circuit breakers are a valuable place for monitoring. Any change in breaker state should be logged and breakers should reveal details of their state for deeper monitoring. Breaker behavior is often a good source of warnings about deeper troubles in the environment. Operations staff should be able to trip or reset breakers.

Breakers on their own are valuable, but clients using them need to react to breaker failures. As with any remote invocation you need to consider what to do in case of failure. Does it fail the operation you‘re carrying out, or are there workarounds you can do? A credit card authorization could be put on a queue to deal with later, failure to get some data may be mitigated by showing some stale data that‘s good enough to display.

原文:https://www.cnblogs.com/toUpdating/p/9521057.html